The Weight Of Hayao Miyazaki And Ghibli – The Boy And The Heron / How Do You Are living?

The uplifting, surreal physics of the animation that creates Hayao Miyazaki’s worlds serve as the foundation for his storytelling. This presents an intriguing contrast to his most recent picture, The Boy and the Heron, which is notably weighted down with emotional, mental, and material burdens as well as the weight of Ghibli’s heritage.

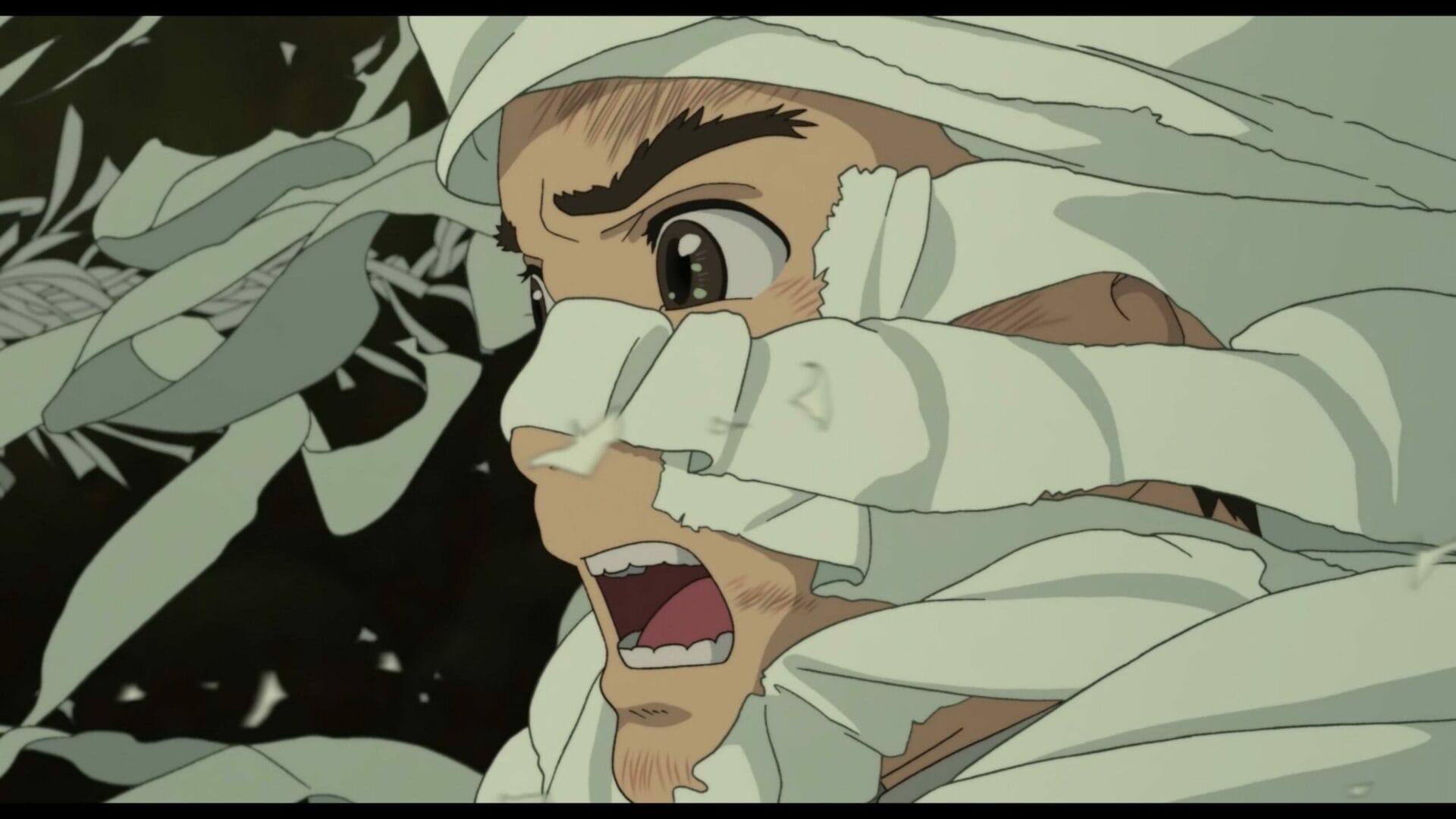

A captivating, eerie fire, animated by Shinya Ohira, culminates the opening sequence of The Boy and the Heron. The blurry, chaotic experience of a child losing his mother in the midst of World War II bombings is captured by his pencil, which is more skilled than anyone else at twisting reality into an expressionist dreamscape. This is one of many autobiographical aspects for director Hayao Miyazaki, as some of his earliest memories are of the war. If the situation seems like it was designed specifically for Ohira’s abilities, that’s because it really is. Veteran actor Toshiyuki Inoue briefly mentions in this interview for Full Frontal that Miyazaki already had him in mind when creating the storyboards. In fact, Ohira himself claims in The Art of The Boy and the Heron that he was the first important animator in the early meetings—apart from one particular supervisor, that is.

Ohira has previously contributed to Miyazaki films, and although the end product is consistently superb, he always felt as though he had to check his pencil texture at the door. His performance in Spirited Away, which aptly gives the impression that Chihiro has entered a completely other universe, is still one of my favorites. When we first encounter Kamaji, his looser forms reflect his animalistic qualities, placing us in the position of a little kid who would be split between the possibility that he could still be her savior and the terrifying sight. Even while it seems like a unique scene, the rest of the movie doesn’t really seem to differ from it. The same can be said for his earlier work with Miyazaki, such as Porco Rosso, and his more recent collaborations, such as The Wind Rises; his iconic portrayal of this trance-like state is astounding and serves as a key component of the character, but even though Ohira created the recipe, it still feels like it uses Miyazaki’s ingredients.

That much is untrue with Ohira’s most recent picture, which is meant to capitalize on the peculiarities of the material. The Boy and the Heron follows protagonist Mahito as he starts to move on from the death of his late mother, but it is not a film about overcoming trauma—at least not as its main theme. Early on, Ohira’s bizarre, unsettling animation repeatedly shows him being haunted by flashbacks of that fire. When he hands over the actual torch to other animators and other settings inside a fantastical universe, fire takes on a much more vibrant role in the hands of artists such as Yoshimichi Kameda. In the end, the great Akihiko Yamashita joyfully animates it to eliminate any last vestige of terror and turn it into an enjoyable mode of transportation. All of this is being used by the younger version of his late mother in an effort to save his new mother and come to terms with her identity. Everything about that character path rests on an initial portrayal of fire that only one person could pull off.

To sum up, the movie’s opening sequence is excellent throughout, and it wasn’t the only moment that I found myself thinking about a lot.

Instead, though it seemed inconspicuous at first, a scenario that followed Ohira’s terrifying spectacle struck a chord with me. Following that painful beginning, we follow Mahito as he makes his way to meet the woman who will become his new mother—none other than the sister of his late mother, which adds a delightful layer of complexity to these connections. The movie implies, though it isn’t explicitly stated, that she comes from an aristocratic family, while Mahito’s father feels nouveau riche after winning big in the armaments trade during the war. Once more, we have a blend of Miyazaki’s personal experiences that relate to his own father’s career and his wider understanding of that historical period. He informed the team that these kinds of marriages were typical at the time, and that less evident anecdotes, like Mahito’s father’s careless donation of funds to the school, were also influenced by his early years.

But the way the animation subtly conveys the severity of this moment is what really makes it powerful. A youngster relocating to a new place is a frequent theme in Miyazaki’s movies, which consistently highlight children’s empathy; nonetheless, The Boy and the Heron expresses tension in a way that sets it apart from its predecessors. Mahito’s acting, rigid but in an overdone, very genuine way, conveys his mixed sentiments of rejection, humiliation, alienation, dread, and so forth as he first sees his new mother Natsuko. And in a single stroke, the entire world of The Boy and the Heron bears the physical weight of that moment.

When Mahito and Natsuko get to where his new home will be, they call a rintaku, which were Japan’s cycle rickshaws of the time. It’s difficult to ignore how incredibly heavy her suitcase is as she hands it off to the cab driver; it really captures the effort required to carry a packed bag of that size. The entire scene is rendered with breathtaking realism, which distinguishes it from the worlds created by Miyazaki. That scene alone should have warned you that this movie has baggage, beyond what the animation can hide. And since that is essential to who it is, it accepts rather than fights that.

Mass. There is an odd connection between it and Miyazaki’s storytelling through his animation. It’s not like he ignores physics, as a great student of the late Yasuo Otsuka. If anything, he has perfected techniques that few others can even begin to consider, let alone pull off, when it comes to making animation consistently dynamic and consequential. But as his career as a filmmaker developed, Miyazaki developed a fondness for rewriting the rules of each of his worlds in accordance with their storylines and tones, consistently leaning toward the fantastical. The overall qualities of its vitality, which conveys life by being bubblier than any actuality, maintain the charm of these locations.

For as long as Miyazaki has served as head director, this much has been the case. When I first watched Future Boy Conan, I found it to be really compelling and even scary at times since, well, I was very young. But what really got me was how the impossible physical feats yet felt like they had a purpose. Its world obviously still maintained boundaries about what was feasible and how bodies should respond to forces, unlike the more exaggerated cartoons I viewed at that age. Those were just different ones, created specifically for this particular adventure—just what you would anticipate from Miyazaki and Otsuka working together. More lightheartedly, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro is comparable in that it establishes the tone for its antics right away with a setpiece that is plainly Otsuka-esque (simply compare Tsukasa Tannai’s physics-bending hurdling to classic Otsuka work in the series).

Flight is a recurrent theme in Miyazaki’s films as he redefines the rules of the universe. He rejected gravity, and it also happened to feed into his complex obsession with aircraft and other flying machines, so you can bet he made a number of films with that concept at the center. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind frequently uses this capacity to characterize its distinct fauna; as a wind-rider, she is the heroine of the valley and her civilization is in harmony with the wind and flying. In fact, her father’s aging is symbolized by his inability to fly. Naturally, Laputa: Castle in the Sky does the same; the first few minutes and opening scene present concepts for defying gravity as it exists now, whether through technological innovations or the magical rules of the setting.

My Neighbor Totoro is the film that, if I had to pick one, best captures Miyazaki’s vision as a storyteller and his animator tendencies together. However, we can quickly observe that Otsuka’s philosophy is still applicable; acts are still significant, they are just not constrained by a realistic set of physics. This is not a departure from the Miyazaki of the past.

Its paradigm has changed, becoming more dreamy in nature, as evidenced by the animation of characters like the soot ghosts and, most prominently, Totoro. I can tell that I’ve conjured up images of the titular creature in many people’s minds just by uttering its title. Totoro is so bouncy and fluffy that, in the famous bus stop scene, a single droplet of water may cause its nose to vibrate. That same scenario serves as a reminder that, despite all of Totoro’s gravity-defying feats, the character still has weight—it just follows its own set of rules. It depicts a universe in which, in addition to animals like the Catbus that can occasionally leap as if they are on the moon, the planet itself occasionally explodes in a way that is both floaty and significant.

In the future, Miyazaki’s filmography will rely heavily on this technique of defining each world’s personality through the physical aspects of the animation. Although they all belong to the same ill-defined category of blobby cartoons, each one’s unique qualities vary depending on the movie’s topics. Ponyo, for instance, begins in the sea, but it soon becomes clear that the animation’s fluid, free-flowing elements are also continuously present on the surface. The animation’s mechanics shift in tandem with Miyazaki’s environmental focus, which is directed towards the ocean.

Similar to this, Kiki’s Delivery Service emphasizes that this theory extends beyond literal weight to include how physical efforts are portrayed. It is a film about flying and literal magic, as well as its absence. Miyazaki’s characters frequently struggle with their physical limitations, therefore they aren’t superhuman. However, he uses exaggeration in a very empowering way to convey things, especially given the large number of children in both his cast and audience. Children identify with films that not only depict fanciful worlds as they envision them, but also feature young characters who, despite physical hardship, are brave and feisty—in many cases, carrying a heap of heavy objects that is almost ludicrous in size.

Not to mention that Miyazaki is drawing lines, which allows him to modify not only the animation style of the film to fit the overall mood but also the demands of individual sequences on an as-needed basis. Even in more subdued ways, like the rhythmic beating in Irontown, you can sense the heavier sense of weight right from the beginning and throughout many important scenes in Princess Mononoke, which may be his most angriest film. However, it never fully turns towards realism. It goes without saying that its fantasy animals are not susceptible to ordinary physics, but what’s really fascinating is how violence and animation qualities relate to one another. When we first witness Ashitaka’s colossal strength, it is from a single arrow shot that slices off two of his arms, pins them to a tree, and sends them flailing around like jello. It’s evident that this planet has equally cartoonish, bouncy laws, even at its most brutal.

When it comes to the modulation of certain properties, Spirited Away is one especially outstanding film. Its lavish, eclectic blend of fanciful concepts establishes its freedom to disregard common sense’s constraints, which extend to the characters’ and the world’s physical limitations. The film features seamless sequences of unrestrained movement, but it also recognizes when to heighten the realism. For instance, a bowl falling more realistically heightens the unease surrounding what has happened to Chihiro’s parents.

Even though, once more, we’re talking about scale modifications rather than binary switch flipping, it’s intriguing to see how those ideas are applied to the most terrifying imaginative creatures Chihiro encounters. Her actions in her first genuine trial at work exhibit more realistic limitations, which eventually give way to totally magical animation once she wins and it’s clear she wasn’t up against a terrifying (or foul-smelling) adversary. The fact that one of the most well-known animation shots is Kaonashi—possibly the most eerie and otherworldly character in the movie—being genuinely carried away by a wave is telling. To say, however, that the modulation is merely used to create a creepier atmosphere would be to do the film a disservice. Yamashita’s realistic falling animation, which has a very humanizing effect in the movie’s emotional climax when people just zoom across spaces, is a feature that you don’t see in movies. This is because Haku has recently been given back his real name, which grounds him in reality, and the animation follows suit.

What was Miyazaki’s most recent significant work up to this year still incorporates all these concepts. In theory, The Wind Rises isn’t even a fantasy tale; rather, it’s a historical drama that retells the narrative of Jiro Horikoshi, a Japanese fighter engineer from World War II. In reality, though, the film is largely about dreaming. The opening scene has a strong physical reaction, but in a dreamlike, floating, fluctuating kind. The fact that those qualities remain in the film long after the characters wake up is difficult to overlook because dreaming never truly ends. The Great Kanto Earthquake, a terrible and very real calamity that retains that enchanted undulation to its animation, is one of the most outstanding examples.

Because The Wind Rises is a film about an engineer, it addresses issues of weight and physical restrictions on a linguistic level, which adds to the appeal of the contrast created by Miyazaki’s decisions. In order to highlight Japan’s technological backwardness, the film repeatedly mentions that their experimental aircraft are pulled by oxen. Jiro states categorically that weight is an issue, so why not just give up the guns? This serves to represent the conflict between his aspirations and the reality of being stuck in the arms industry. All of this knowledge is insufficient to visibly burden Jiro’s dreams; rather, the sequences that bring him and his wife Nahoko closer highlight those qualities—albeit admittedly in an overly dramatic manner. The one bond that keeps him grounded in a film about living in the world of dreams is similarly animated.

As Jiro and Nahoko meet at the station in one of the film’s last sequences, Miyazaki’s buoyancy is expertly blended with more realistic aspects. Takeshi Honda, who gained the moniker “master” in the anime industry in a matter of years, is credited with key animating it. He went on to take credit for it in a way that I doubt even his original source could have expected. As someone who was raised at Gainax and has a talent for both mecha and character animation, Honda’s animation has always had that bounce to it. However, he’s also someone who not only competes with the nation’s most renowned realist animators, but frequently finds himself in the lead; a true shishou, he’s a jack of all trades and somehow a master of them all.

He had always wanted to help Miyazaki with his skills, and at the pivotal point of Ponyo, he was able to fulfill this desire and gain the elusive, highly sought-after praise from the director. Following his triumphant performance in The Wind Rises, he received an invitation to serve as the animator for Boro the Caterpillar, a short film that was only available at the Ghibli Museum and Park. While they were finishing up that project, Miyazaki called him aside to discuss a more ambitious role that coincided with Honda’s intention to direct the last Evangelion movie. Miyazaki’s insistence that he focus on his project and complete it immediately caused him to abandon his previous plans, as he has explained in a number of interviews, varying in candor depending on the platform. A legend who was close to that number and exceeded it with this production does not make a pitch that you want to reject. “No one in my family has lived over 80 years, we gotta do this now.”

Naturally, The Boy and the Heron is the project under discussion. I was moved by Honda’s own important animation in that scene, and his careful direction permeates the whole film with similar elements. Mahito makes tangible imprints at every significant turn, and his troubles have a corresponding physical dimension. Even in a film featuring the titular mythical bird, we witness him clumsily fall under the weight of a greater gravity than in previous Miyazaki works. The Miyazaki paradigm is reshaped by Honda’s position as the team’s chief animator and the presence of a few more logical realists than usual.

Naturally, the keyword there is readjusted. Similar to how treating earlier movies as a purely cartoonish dream was a mistake, The Boy and the Heron hasn’t exactly given up on its bouncy Miyazaki-ness—rather, it’s just toned it down. Toshio Suzuki, a well-known storyteller, has spoken about the film as though he has given up on the animation project, but that is Miyazaki’s language and he just needs to do his films. Even though he might not be in complete control of every crucial animation frame as he previously was, his concept work, designs, and constant layouts all have a magical quality to them, and he still animated a few important scenes himself.

The most visually arresting instance of this amicable conflict between various approaches occurs when Mahito, feeling excluded at his new school due to his father’s inability to read social cues, strikes himself in the head with a rock to give an excuse for missing class. Even on its own, the impact is profound, and little details like the way the blood practically grounds the plant at his feet add to the unsettling effect. Even though Yamashita’s original art was superb, Miyazaki nonetheless stepped in to ensure that the blood flow was emphasized in the same way that older Ghibli films would highlight large, blobby tears. The end product is astounding, a mash-up of ideas that essentially captures the visual breadth of this movie.

A viewer familiar with Miyazaki’s body of work will notice that the film begins to highlight various forms of weight in addition to physical weight. Regardless of how you interpret it, the first scenario I emphasized is a psychological burden that Mahito must eventually learn to bear. Other main characters, such as Natsuko, go through storylines in which they must resist being crushed by a variety of burdens, such as having to take on the role of her own captivating sister as a wife and mother. She feels particularly vulnerable to the weight of motherhood because she is not only adopting Mahito but also expecting a child of her own. Once again, Honda’s key animation masterfully raises the reality as she finally lets loose about everything, expressing both rejection and concern for Mahito.

Physical weights, such as the one from the suitcase she brought to the first meeting, overlap with symbolic ones; inside were a variety of goods like cigarettes and white sugar, which became more and more difficult to come by during the war, making the suitcase literally worth its weight in gold. Weight, weight, weight in every direction. Miyazaki’s redesigned role amplifies its visual expression, but even that is part of the film itself, which has a very distinct sense that only an aging mastermind burdened by their own heritage could make.

Similar to how the first half of the movie is obviously filled with autobiographical details about Mahito, the second part of the movie blatantly depicts his current status as a creator. During his quest to save Natsuko, Mahito finds himself in a fanciful universe that has evolved around a single figure: the creator, who is too elderly to keep up with the regular tweaking required to maintain the viability of an empire the size of Ghibli’s. That individual must wonder how to get a successor from his own lineage and whether it is really required, just as he did. It’s pushed to the fore to the point where it’s difficult to even label it metatextual—Miyazaki’s career and Ghibli’s importance are ultimately what it comes down to. Additionally, his choice to aggressively pursue Honda at the outset and the themes’ alignment feel like they can’t be coincidences because he is a cunning director who, at this time, exclusively hires individuals whose abilities he knows very well.

That makes the movie’s ending all the more intriguing. Mahito ultimately declines to take the throne, citing the weight of his cowardly, self-inflicted wound as evidence of human dirtiness—that is, something unworthy of the purity of a fantasy world but rather of the human realm. The Boy and the Heron make movements that suggest a message of hope for the future, accepting the imperfections that come with being human. The physical limitations—or rather, the absence of them—in the animation serve to emphasize that point once more. Almost every character in the film—including the numerous birds—is burdened by gravity at some point during the narrative. The Warawara, who, according to Kiriko, rise up to the real world to take on human form after being fed, are the only ones that defy this law. It seems logical that the only floating creatures in the movie are those who existed before life, assuming Mahito is correct and to live is to sin and be burdened by human nature.

Ultimately, the tower of creativity crumbles beneath its own weight. the burden of aging and, possibly, an abundance of outside influences that have gotten out of hand. The existence of invading species, who are taken somewhere they don’t belong against their will and natural impulses but are nevertheless worthy of life despite their potentially harmful position in such ecosystems, is Miyazaki’s take on the environment in this film. The parakeets that have taken over this place of creation are the most noticeable of all. Friends of mine have compared them to the merchandise empire that has grown around Ghibli themselves, who at times have been more of a Totoro plushie factory than an animation studio. They are colorful, funny, but also dumb, incapable of meaningful creation themselves, and yet always hungry. Perhaps there is no reason to be fixated on preserving Ghibli if that is where things stand.

This film can be interpreted in a variety of ways since it is just too intricate to accurately link each allegory to a single, meaningful idea. It is ultimately quite interesting because of the many opposing notions that coexist in it. The Boy and the Heron is undoubtedly not Miyazaki’s most technically flawless work, but it is unquestionably his most significant due to its discussion of the director’s vast body of work and how its animation relates to many of those concepts.